Export PostgreSQL data to CSV with Django

Introduction

One day, the product manager at the company I was working for came to me with what sounded like a walk in the park. “Can you add a button,” he said, “so I can export some database data for KPIs?”

Sure. Easy win. I added the button, pushed the code, and everyone walked away smiling. It felt like the stars had aligned.

But as anyone who’s been in this business knows, software has a habit of hiding landmines under freshly paved roads.

The very next day, the same product manager came back, wearing that familiar look the one that says something went wrong, and it’s probably your fault.

“When I press the button,the app freezes… and then crashes.”, he said.

Of course it did. Because in our line of work, nothing is ever just a button. What looks like a simple click can turn into a runaway freight train once it hits the database.

Still, we live and learn. We trip, we debug, we refactor. So let’s tell this story the right way, one where the developer sharpens their tools, the project manager sleeps at night, and the readers walk away wiser than before. Because after all, every crash is just a lesson in disguise wrapped in a stack trace.

Case Overview

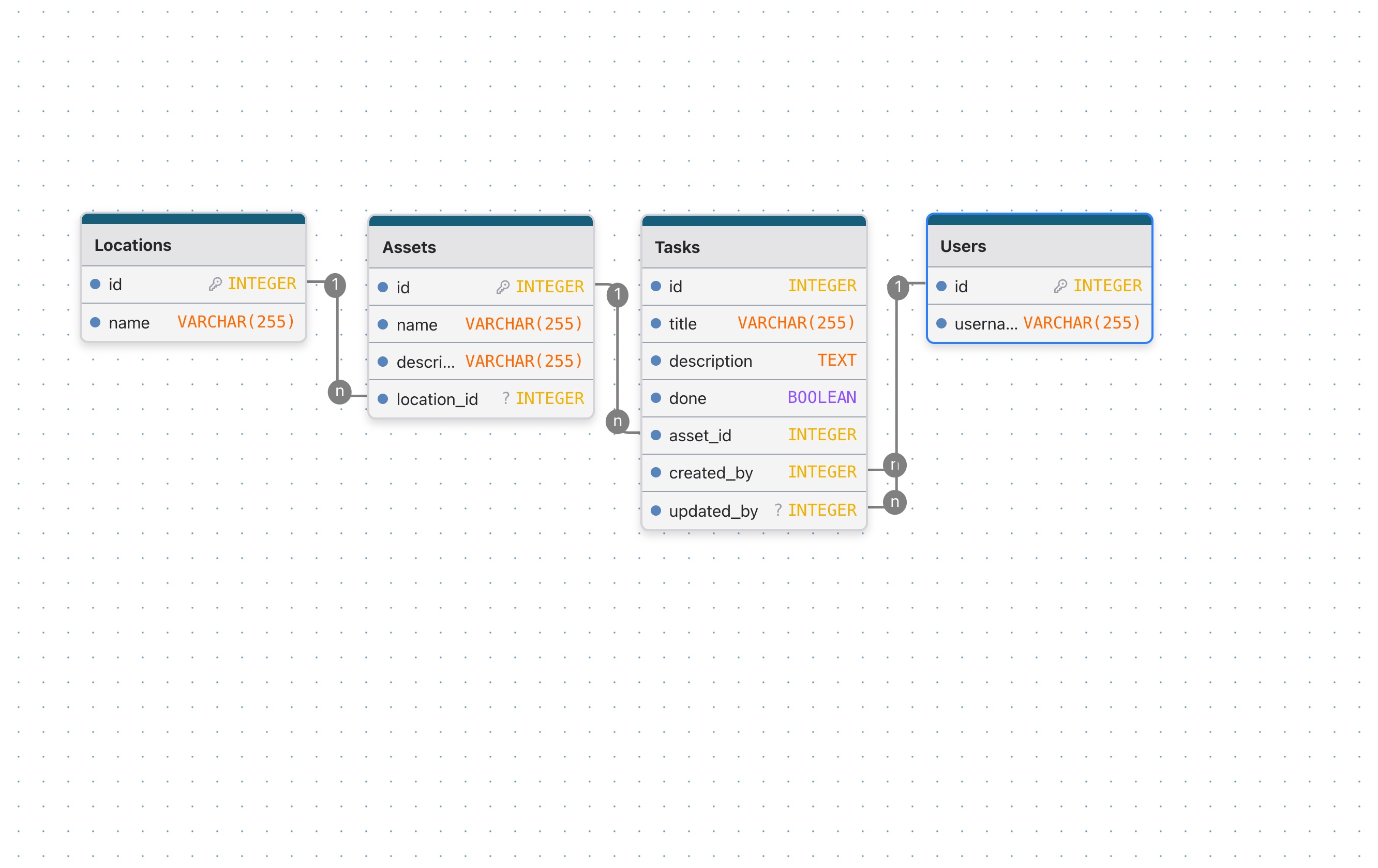

Let's imagine we have a CMMS system. Here, we'll take the simplest case. We have a locations table, an assets table, a task table, and a table to display the users who in charge to the tasks.

Models

from django.db import models

class Location(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

class Meta:

db_table = "locations"

class Asset(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

description = models.TextField()

location = models.ForeignKey(

to=Location, on_delete=models.PROTECT, related_name="assets"

)

class Meta:

db_table = "assets"

class Task(models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=100)

description = models.TextField()

done = models.BooleanField(default=False)

asset = models.ForeignKey(to=Asset, on_delete=models.PROTECT, related_name="tasks")

created_by = models.ForeignKey(

to="User", on_delete=models.PROTECT, related_name="+"

)

updated_by = models.ForeignKey(

to="User", on_delete=models.PROTECT, related_name="+", null=True

)

class Meta:

db_table = "tasks"

class User(models.Model):

username = models.CharField(max_length=100)

class Meta:

db_table = "users"

Data seed

Below is a complete Django management command to create 50 Locations, 100 Users, 300 Assets, and 100000 tasks

import random

from django.db import transaction

from django.utils import lorem_ipsum

from django.core.management.base import BaseCommand

from cmms.models import Location, Asset, Task, User

class Command(BaseCommand):

help = "Seed database with locations, assets, users and tasks"

def handle(self, *args, **options):

self.stdout.write("Seeding data...")

with transaction.atomic():

# USERS

users = [User(username=f"user_{i}") for i in range(1, 101)]

User.objects.bulk_create(users)

users = list(User.objects.all())

# LOCATIONS

locations = [Location(name=f"Location {i}") for i in range(1, 51)]

Location.objects.bulk_create(locations)

locations = list(Location.objects.all())

# ASSETS

assets = [

Asset(

name=f"Asset {i}",

description=lorem_ipsum.words(100),

location=random.choice(locations),

)

for i in range(1, 301)

]

Asset.objects.bulk_create(assets)

assets = list(Asset.objects.all())

# TASKS (100,000)

tasks = []

for i in range(1, 100_001):

created_by = random.choice(users)

# ~70% tasks are done

done = random.random() < 0.7

# updated_by is NULL about 40% of the time

updated_by = None

if random.random() < 0.6:

updated_by = random.choice(users)

tasks.append(

Task(

title=f"Task {i}",

description=lorem_ipsum.words(100),

done=done,

asset=random.choice(assets),

created_by=created_by,

updated_by=updated_by,

)

)

# Bulk insert in chunks to avoid memory issues

if i % 5000 == 0:

Task.objects.bulk_create(tasks)

tasks.clear()

self.stdout.write(f"Inserted {i} tasks")

if tasks:

Task.objects.bulk_create(tasks)

self.stdout.write(self.style.SUCCESS("Seeding completed"))Metrics

Throughout this article we are interested in two main metrics: time and memory.

Measuring Time

To measure time for each method we use the built-in time module:

>>> import time

>>> start = time.perf_counter()

>>> time.sleep(1) # do work

>>> elapsed = time.perf_counter() - start

>>> print(f'Time {elapsed:0.4}')

Time 1.001The function perf_counter provides the clock with the highest available resolution, which makes it ideal for our purposes.

Measuring Memory

To measure memory consumption, we are going to use the package memory-profiler.

pip install memory-profiler

#or

uv add memory-profilerThis package provides the memory usage, and the incremental memory usage for each line in the code. This is very useful when optimizing for memory. To illustrate, this is the example provided in PyPI:

$ python -m memory_profiler example.py

Line # Mem usage Increment Line Contents

==============================================

3 @profile

4 5.97 MB 0.00 MB def my_func():

5 13.61 MB 7.64 MB a = [1] * (10 ** 6)

6 166.20 MB 152.59 MB b = [2] * (2 * 10 ** 7)

7 13.61 MB -152.59 MB del b

8 13.61 MB 0.00 MB return aThe interesting part is the Increment column that shows the additional memory allocated by the code in each line.

In this article we are interested in the peak memory used by the function. The peak memory is the difference between the starting value of the "Mem usage" column, and the highest value (also known as the "high watermark").

Metrics Middleware

To put it all together, we create the following middleware to measure and report time and memory:

# app/middleware.py

import time

from memory_profiler import memory_usage

class RequestTimingMiddleware:

def __init__(self, get_response):

self.get_response = get_response

def __call__(self, request):

start_time = time.perf_counter()

def run_view():

return self.get_response(request)

mem_usage, response = memory_usage(

(run_view, ()),

interval=0.01,

timeout=None,

retval=True,

max_usage=True,

)

total_time = time.perf_counter() - start_time

print(f"time={total_time:.2f}s " f"peak_mem={mem_usage:.2f}MiB")

return responseWhat are we trying to achieve ?

For testing and benchmarking purposes, our task is to extract the following information into a CSV file:

- the task ID

- its title,

- the asset name and its location,

- the status (Done / Not Done),

- the name of the user who created the task,

- and the name of the user who last modified it, if it has been modified.

First Solution using .all()

import csv

from django.http import HttpResponse

from . import models

def get_tasks(request):

res = HttpResponse(content_type="text/csv")

writer = csv.writer(res)

writer.writerow(

("Id", "Title", "Asset", "Asset Location", "Done", "Created By", "Updated By")

)

tasks = models.Task.objects.select_related(

"asset", "asset__location", "created_by", "updated_by"

).all()

print(tasks.query)

for task in tasks:

writer.writerow(

[

task.pk,

task.title,

task.asset.name,

task.asset.location.name,

task.done,

task.created_by.username,

task.updated_by.username if task.updated_by else None,

]

)

return restime=2.01s peak_mem=614.06MiBSELECT "tasks"."id", "tasks"."title", "tasks"."description", "tasks"."done", "tasks"."asset_id", "tasks"."created_by_id", "tasks"."updated_by_id", "assets"."id", "assets"."name", "assets"."description", "assets"."location_id", "locations"."id", "locations"."name", "users"."id", "users"."username", T5."id", T5."username" FROM "tasks" INNER JOIN "assets" ON ("tasks"."asset_id" = "assets"."id") INNER JOIN "locations" ON ("assets"."location_id" = "locations"."id") INNER JOIN "users" ON ("tasks"."created_by_id" = "users"."id") LEFT OUTER JOIN "users" T5 ON ("tasks"."updated_by_id" = T5."id")Second Solution using .values()

Since there is no need to manipulate Django model instances, the required data can be retrieved directly from the database. Therefore, when exporting to CSV, using .values() is sufficient and preferable to .all(), as it allows us to fetch only the necessary fields without instantiating full model objects.

import csv

from django.http import HttpResponse

from . import models

def get_tasks_values(request):

res = HttpResponse(content_type="text/csv")

writer = csv.writer(res)

writer.writerow(

("ID", "Title", "Asset", "Asset Location", "Done", "Created By", "Updated By")

)

tasks = tasks = models.Task.objects.values(

"id",

"title",

"asset__name",

"asset__location__name",

"done",

"created_by__username",

"updated_by__username",

)

print(tasks.query)

for task in tasks:

writer.writerow(list(task.values()))

return restime=0.58s peak_mem=282.92MiBSELECT "tasks"."id" AS "id", "tasks"."title" AS "title", "assets"."name" AS "asset__name", "locations"."name" AS "asset__location__name", "tasks"."done" AS "done", "users"."username" AS "created_by__username", T5."username" AS "updated_by__username" FROM "tasks" INNER JOIN "assets" ON ("tasks"."asset_id" = "assets"."id") INNER JOIN "locations" ON ("assets"."location_id" = "locations"."id") INNER JOIN "users" ON ("tasks"."created_by_id" = "users"."id") LEFT OUTER JOIN "users" T5 ON ("tasks"."updated_by_id" = T5."id")Third Solution using .iterator()

Using iterator() when working with Django QuerySets allows records to be fetched in chunks directly from the database, rather than being fully loaded into memory at once. This significantly reduces memory consumption, especially when handling large datasets such as those involved in CSV exports or data processing tasks.

Additionally, iterator() bypasses Django’s QuerySet caching mechanism, ensuring that each row is processed only once. This makes it particularly suitable for streaming operations and improves overall performance and scalability when dealing with large volumes of data.

def get_tasks_values_iterator(request):

res = HttpResponse(content_type="text/csv")

writer = csv.writer(res)

writer.writerow(

("ID", "Title", "Asset", "Asset Location", "Done", "Created By", "Updated By")

)

tasks = tasks = models.Task.objects.values(

"id",

"title",

"asset__name",

"asset__location__name",

"done",

"created_by__username",

"updated_by__username",

).iterator(chunk_size=2000)

for task in tasks:

writer.writerow(list(task.values()))

return restime=0.59s peak_mem=113.88MiBFourth Solution using COPY

Django QuerySets are lazy, but they have a .query attribute representing the SQL. To see the raw SQL string:

qs = models.Task.objects.values(

"id",

"title",

"asset__name",

"asset__location__name",

"done",

"created_by__username",

"updated_by__username",

)

print(str(qs.query))

SELECT "tasks"."id" AS "id", "tasks"."title" AS "title", "assets"."name" AS "asset__name", "locations"."name" AS "asset__location__name", "tasks"."done" AS "done", "users"."username" AS "created_by__username", T5."username" AS "updated_by__username" FROM "tasks" INNER JOIN "assets" ON ("tasks"."asset_id" = "assets"."id") INNER JOIN "locations" ON ("assets"."location_id" = "locations"."id") INNER JOIN "users" ON ("tasks"."created_by_id" = "users"."id") LEFT OUTER JOIN "users" T5 ON ("tasks"."updated_by_id" = T5."id")str(tasks.query) gives the SELECT statement with all joins from .values().

Wrapping it in COPY (...) TO STDOUT WITH CSV makes it directly compatible with PostgreSQL’s COPY.

from django.db import connection

def get_tasks_values_copy(request):

# Prepare HTTP response

response = HttpResponse(content_type="text/csv")

response["Content-Disposition"] = 'attachment; filename="tasks.csv"'

response.write(

",".join(

(

"ID",

"Title",

"Asset",

"Asset Location",

"Done",

"Created By",

"Updated By",

)

)

+ "\n"

)

# Build the QuerySet

tasks = models.Task.objects.values(

"id",

"title",

"asset__name",

"asset__location__name",

"done",

"created_by__username",

"updated_by__username",

)

# Convert QuerySet to raw SQL string

raw_sql = str(tasks.query)

# Wrap in COPY statement

copy_sql = f"COPY ({raw_sql}) TO STDOUT WITH CSV"

# Stream CSV directly to response

with connection.cursor() as cursor:

cursor.copy_expert(sql=copy_sql, file=response)

return responsetime=0.24s peak_mem=80.61MiBSummary

| Method | Time | Memory |

|---|---|---|

| .all() | 2.01s | 614.06MiB |

| .values() | 0.58s | 282.92MiB |

| .values().iterator() | 0.59s | 113.88MiB |

| COPY query | 0.24s | 80.61MiB |

Conclusion

In this project, multiple approaches were explored to export task data from Django to CSV. Initially, retrieving all task objects with .all() and writing them in Python using the csv module proved straightforward but inefficient, as it instantiated full model objects for each row. Switching to .values() and .values_list() allowed selecting only the required fields, returning dictionaries or tuples instead of full objects, which reduced memory usage and simplified the SQL queries. Finally, generating the raw SQL from the QuerySet and using PostgreSQL’s COPY ... TO STDOUT command enabled direct CSV export from the database, eliminating the need for Python-level iteration and improving overall performance for large datasets.